Unravelling the mysteries of in-depth psychological profiling

March 31, 2015

As a business psychologist, one of my main activities is in-depth psychological profiling of people. It’s not the only thing I do but it’s certainly a big part of my job. What I’ve realised when I talk to people, however, is that they don’t really understand what I mean by it. So this month I thought I’d go back to basics and explain just what psychologists do when we profile someone. And now I’ve muddied the waters again with a picture of a couch. Sadly, there’s no couch.

What’s it for?

The aim of assessing someone in this way is to get as clear a picture of them as possible. How much complexity can they handle? Can they think strategically? What are they like at their best and their worst? How are they likely to interact with others? How do they handle conflict? Can they inspire people? Do they cut corners? And so on and so on. The questions are endless.

Very occasionally I do this on behalf of the person being assessed, perhaps as part of their professional development. But usually someone else is paying me. Often it’s a company recruiting at a senior level but it could also be to highlight someone’s strengths and development needs prior to coaching, to identify and nurture talent in the organisation or for succession planning purposes. I’ve even assessed entire management teams on behalf of private equity firms prior to them agreeing to invest in a company. It’s really used in any situation where an organisation wants to get a very clear picture of an individual.

Here’s what I’m not doing

Firstly, I’m not assessing whether technically someone can do the job or has the right level of knowledge or experience.  People in the organisation are much better placed than I am to know whether someone is a good Finance Director or IT specialist or has enough knowledge of the packaging industry or whatever. I’ve profiled everyone from geophysicists in the mining industry to chaplains in the armed forces. I cannot possibly understand the technicalities of each person’s job. That’s not my role. My role is to figure out who shows up at work to do that job.

People in the organisation are much better placed than I am to know whether someone is a good Finance Director or IT specialist or has enough knowledge of the packaging industry or whatever. I’ve profiled everyone from geophysicists in the mining industry to chaplains in the armed forces. I cannot possibly understand the technicalities of each person’s job. That’s not my role. My role is to figure out who shows up at work to do that job.

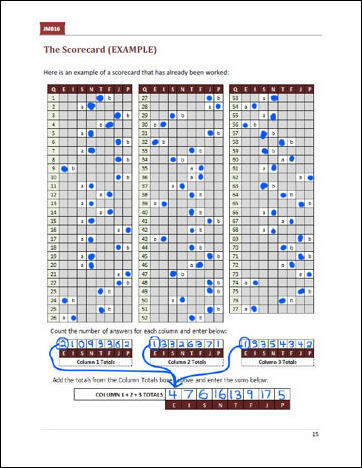

The second thing I’m not doing is identifying a person’s ‘psychological type’. By this I mean things like Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) or the Insights Colour Profiling system. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of MBTI and find it incredibly useful in team building situations, where it provides a simple, yet sophisticated, framework for helping people to recognise that other people do not see the world as they do. But this kind of tool is entirely unsuited (and actually prohibited) for use in assessment and selection. My aim in profiling is not to say, for example, “he’s an ESTJ and this is what ESTJs are like”. It’s to provide a rich and nuanced picture of what this person is like.

So how do I do it?

My starting point is to get some data from psychometric assessments (personality test, cognitive assessment, ‘shadow side’ profile and maybe a motivations indicator), which I can then explore with the person. I have to confess that I bristle slightly when people say things like “Oh you do psychometric testing”, as though all I do is put someone through a test and read the results.

I have to confess that I bristle slightly when people say things like “Oh you do psychometric testing”, as though all I do is put someone through a test and read the results.

If you want to ‘do a psychometric test’ there are plenty of systems out there that will generate a report, telling you that you that ‘John is about as outgoing as most people’ or ‘Laura is meticulous with detail and may have perfectionist tendencies’. It’s not that this information isn’t useful but it’s the starting point not the end product. It’s the way we explore, analyse and synthesise that information to build up a picture that’s the difference between a psychologist and a computer program.

Let’s bring it to life

Take, for example, a senior manager in a very technical industry applying for a new job. We’ll call him Pete. Take it as a given that he has the right technical experience and qualifications. Some of the things (amongst many others) that the psychometrics reveal about Pete are that he values expertise built up over time, he’s very team-oriented, extremely modest and somewhat mistrustful of others. With that basic data, do you want to hire him? Hard to say, isn’t it?

Very careful questioning shows how that all plays out in the workplace. Pete builds very close-knit teams of technical experts, who enjoy great camaraderie and constantly innovate technically. But you either fit in the team or you’re ostracised. If you can’t cut it technically, you’re out. If you talk openly about your achievements, you don’t fit – Pete will assume that you’re not very good at your job. He’s very modest, remember, and believes the quality of the work should speak for itself. So why are you having to do it? And don’t even think about managing Pete if you’re not a technical expert yourself. Never mind if it’s your company or you have a strategic perspective and can see where the technology fits into the organisation’s future direction. In Pete’s eyes, if you haven’t spent years honing your technical skills, you will never understand his job properly and have no authority to tell him what to do.

Pete builds very close-knit teams of technical experts, who enjoy great camaraderie and constantly innovate technically. But you either fit in the team or you’re ostracised. If you can’t cut it technically, you’re out. If you talk openly about your achievements, you don’t fit – Pete will assume that you’re not very good at your job. He’s very modest, remember, and believes the quality of the work should speak for itself. So why are you having to do it? And don’t even think about managing Pete if you’re not a technical expert yourself. Never mind if it’s your company or you have a strategic perspective and can see where the technology fits into the organisation’s future direction. In Pete’s eyes, if you haven’t spent years honing your technical skills, you will never understand his job properly and have no authority to tell him what to do.

As you can see, Pete has some great skills and some major drawbacks. Whether you hire him or not is up to you and might depend on your own background and management style, the situation the organisation is in and what other options you’ve got. But if you do take him on, at least you know who you’re getting and will have a better idea of how to manage him.

And that’s kind of the point. You’re very unlikely to find the perfect candidate for a job. But a well-conducted psychological assessment can help you identify the ones whose strengths are a real asset, whose weak points you can live with and whose risks you can manage.

If you’d like to talk about using psychological profiling in your organisation, I’d be happy to have a chat: caroline@carolinegourlay.co.uk

Photo credits

Psychologist: Drew Leavy

Technician – Argonne National Laboratory

Psychometrics: Richard Stephenson

Team: Creative Sustainability